The International Society for Cell & Gene Therapy (ISCT) facilitated a webinar on December 6, 2023, chaired by Jeff Litter, featuring David Hermanson (Bio-Techne) and Farzin Farzeneh (Virocell), to discuss viral and non-viral gene delivery methods, as well as how to go about sourcing a CDMO.

There were many insights into the pros and cons of each method. The panel then shared some interesting questions they commonly receive during the CDMO sourcing process, and some they don’t hear often but should! (What’s your turnover rate and does it affect consistency and quality?)

Essential Considerations for Choosing a CDMO

Here are a few of the more common considerations the panel recommended:

- What type of vector are you interested in?

- What level of design support do you need and how is it optimized?

- Are manufacturing slots available in the timeframe you need?

- How can you de-risk your project and demonstrate that it works in your cells of interest?

- What’s the ethos of the CDMO? Does it regard your issues as its own?

- How scalable is the manufacturing process, especially for plasmids and RNA?

- How knowledgeable is the team?

Uncovering the Link Between T Cell Malignancy and Gene Delivery

The conversation soon turned to the FDA’s recent comments and investigation into T cell malignancy following BCMA-directed or CD19-directed autologous CAR-T cell immunotherapies1 and a causal link with vectors and gene delivery methods.

Overall, the panel was surprised at the alarm around the FDA statements and gave context to the situation with the analogy of buying lottery tickets, i.e., if you buy all the lottery tickets, you will win. However, only 0.5% of patients demonstrated undesirable effects, which is a credit to the field that so many thousands of patients have been treated, who would otherwise have no other therapeutic option.

A key characteristic of lentiviral vectors is, of course, that they integrate into the host genome, which is passed onto progeny. Off-target integrations and high copy numbers can increase the risk of these secondary malignancies, but the field is working on solutions to this, as patient safety is paramount in the cell and gene therapy industry.

Farzin is passionate about autoregulated vectors that will enable spontaneous induction of self-destruction in the case of undesirable outcomes. These vectors are responsive to environmental conditions with safety switches more akin to a smoke alarm. Theoretically, they prevent secondary malignancies but are a year or two away from the clinic.

So, let’s evaluate non-viral methods.

Exploring the Potential of Non-Viral Gene Delivery Methods

David referenced the study Micklethwaite, Kenneth P., et al. Blood (2021)2, which found two transformation events of malignancy: one had a copy number of 26 and the other was 4. This begs the question, does copy number matter in the context of non-viral vectors? The authors of the study hypothesized that their production methodology, in which they used harsh electroporation conditions and expanded with irradiated PBMCs, was the predominant factor leading to the transformations. Furthermore, the authors noted that other groups have not observed any suggestion of transformation using transposon systems with different production processes and >2-year follow-up in patients.

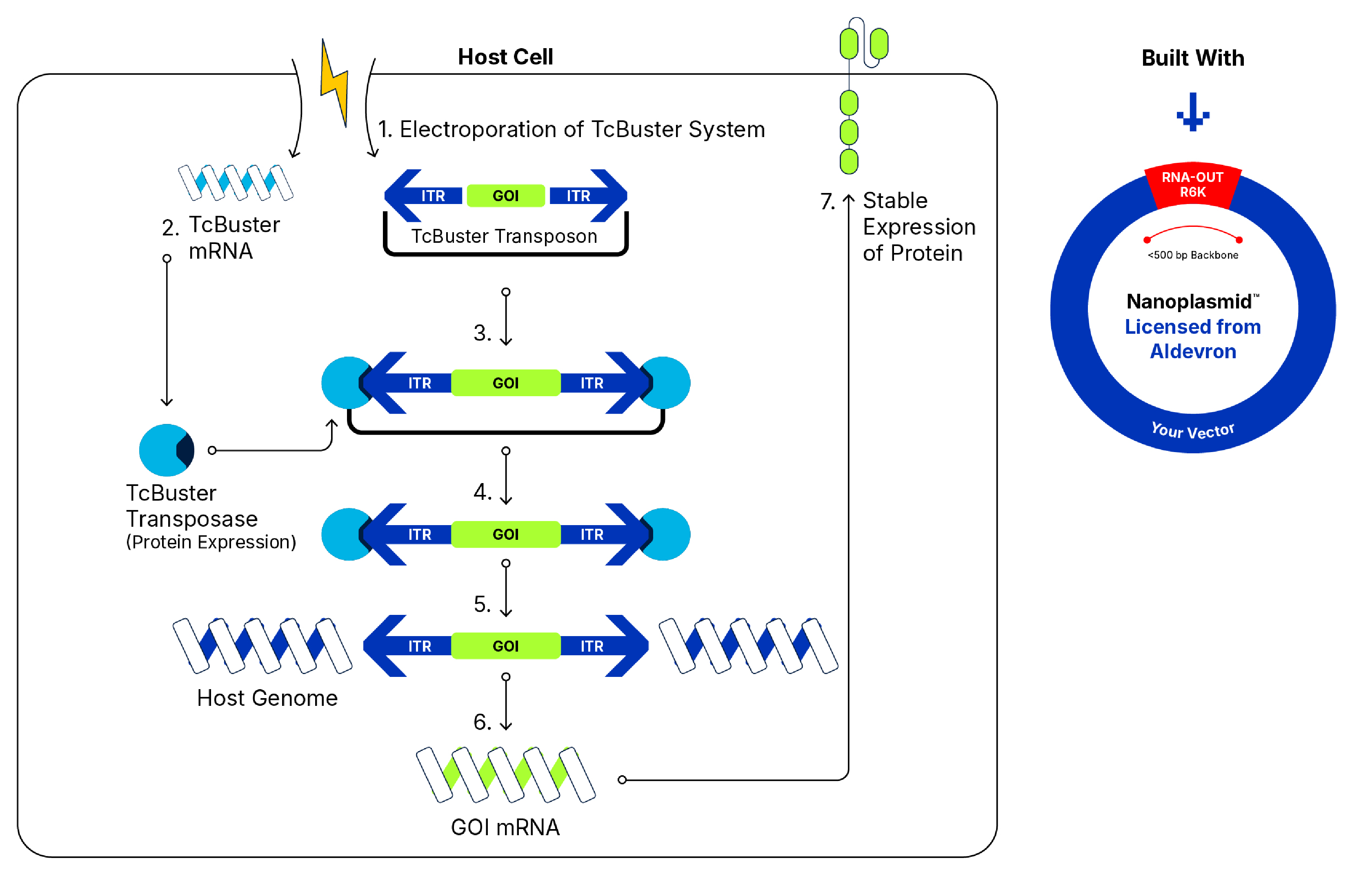

In studying TcBuster™, our non-viral gene delivery platform, it is possible to control copy number through titration of the transposon amount, as well as through electroporation parameter optimization. Through assessing the optimization of electroporation on different technologies, we have been able to consistently edit T cells with average copy numbers in the range of 4-7.

During electroporation and gene delivery, any time there is a double-strand break, the transposon holds on to both ends while inserting the gene of interest, so it can be deduced that there is a reduced chance of chromosomal instability. In addition, target site integration is more random for transposon delivery than it is for viral vectors, as it is less likely to insert into introns and exons or other regions in the genome that are related to gene expression. In contrast, viral vector methods insert more consistently into active chromatin regions.

The Future of Gene Delivery: Balancing Innovation and Safety

David concluded that non-viral methods have improved integration profiles, and the field should have more conversations about what an acceptable copy number is for a transposon system specifically. As copy number is a release criterion, any new evidence could significantly impact manufacturing.

It’s clear that innovation is needed, and thankfully underway, from viral and non-viral technologies. Autoregulated viral vectors and a better understanding of the impact of copy numbers could improve patient access and safety.

Hear more from David Hermanson as he discusses how flexible, scalable non-viral manufacturing of gene-modified CAR-T therapies can be achieved, using TcBuster, in this talk, originally presented at Advanced Therapies Week 2024.

Learn More About TcBuster »

-

(2023) FDA Investigating Serious Risk of T-cell Malignancy Following BCMA-Directed or CD19-Directed Autologous Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR) T cell Immunotherapies U.S. Food & Drug Administration

-

Micklethwaite, Kenneth P et al. (2021) Investigation of product-derived lymphoma following infusion of piggyBac-modified CD19 chimeric antigen receptor T cells Blood 13816:1391–1405.